The crazy, true-life adventures of Norway’s most radical billionaire

I read this on Fortune and was inspired by how this man came about. So here is an inspiring story.

Fred Olsen is both the owner of Timex and its most successful watch designer. He’s also a world-class sailor and an oil industry pioneer, and was rumoured to have inspired a Simpsons character. Now he’s leading a revolution in offshore wind.

Fred Olsen is reliving the day he ran off to sea. The 86-year-old Norwegian billionaire is showing me around the museum-like headquarters of his business empire when he pauses next to a glass-encased model of the Bruno, the fruit ship he boarded in January 1949, just days after his 20th birthday. As the scion of a Norwegian shipping empire co-founded by his great-grandfather and named for his great-granduncle, the original Fred Olsen, he could have taken the predictable path of the privileged. His own father, Thomas, had attended Cambridge and run the family business despite never having worked on a ship. But Olsen decided to chart his own course. Instead of attending college, he spent more than two years touring the world aboard the Bruno and other vessels, shipping bananas from the Canary Islands to Scandinavia and cognac from Bordeaux to the Mediterranean. He labored in lowly positions, as a deck hand and a “greaser,” the sailor who fixes the auxiliary engine that generates electricity. Along the way he studied the boats’ mechanical systems and observed how cargo was managed. “It was better than an MBA, better than an engineering degree,” says Olsen, his pale-blue eyes, framed with rimless glasses, twinkling as he recalls life on the Bruno. “No diploma could come close to that education.”

The world of business is not populated with many truly unconventional thinkers—except, of course, at the top of some of its most revolutionary companies. Think of other non–college grads who took a radical approach and stuck to it fearlessly: Steve Jobs created world-changing products at Apple. Bill Gates followed his passion for programming to build Microsoft, the world’s largest software company. And Sir Richard Branson has battled the establishment in everything from music to airlines.

Like them, Olsen is a dreamer who acts—and rarely follows the expected script. Heir to a shipping fortune, Olsen steered the family businesses in a new direction, first leading the North Sea oil revolution, then becoming one of the world’s foremost pioneers in wind power. But that’s just the beginning of his story. Given his over-the-top life experiences, maybe it’s Olsen, not the bearded adventurer from the Dos Equis beer commercials, who is really “The Most Interesting Man in the World.”

In the late 1960s, Olsen led the first Norwegian group to drill for oil in the North Sea. Shortly thereafter, his company’s rig made the first discovery in Ekofisk, one of the largest deepwater oilfields ever developed. Olsen also co-founded Norway’s first private oil company, Saga Petroleum, and rallied the Norwegian industry to build expertise in oilfield products and services, a course that helped make his homeland one of the richest nations on earth.

Since he branched out into renewable energy in the 1990s, Olsen’s companies have invested more than $1 billion in wind power. Olsen is now the biggest independent, meaning non-utility, provider of wind electricity in Britain. Today he’s focusing on the fastest-growing market in renewables: offshore wind. His companies installed one in five new offshore turbines last year in Europe, the world’s largest market. He’s also installing the first sea-based wind farm in the U.S., located off the coast of Rhode Island.

When he’s not disrupting the energy industry, Olsen doubles as one of history’s most successful watch designers. He and his daughter Anette, 58, control and run Timex Group, which has struggled a bit lately but still ranks as the No. 2 seller of watches in the U.S., behind Fossil. It was Olsen himself who practically created the sports watch category when he dreamed up the best-selling Ironman Triathlon in the mid-1980s. A few years later he brought illumination to watches with the Indiglo night-light. And in 1994 he launched a groundbreaking “smart watch,” the Data Link, co-developed with Microsoft.

As befits a man who once ran off to sea, Olsen is also a world-class sailor. He won the world championship in International One Design, a class of 33-foot boats, in 1959 and 1960. After a break lasting decades he staged a comeback, finishing a promising third, in a tight finish, in the 2014 Norwegian championships. As a concession to his age, these days he wears a construction helmet onboard. “I need protection because I keep getting hit by the boom,” he explains.

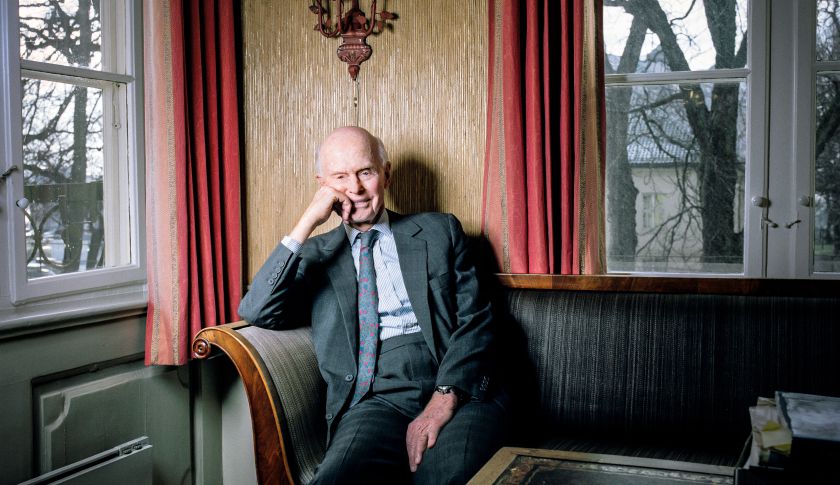

Olsen’s story is not well known, in part because—despite owning Norway’s largest business newspaper publisher—he has spent most of his long career avoiding the media spotlight. Recently he granted Fortune the first extensive interviews he’s ever conducted. In the course of almost two full days of conversations in his offices—housed in a building constructed in 1710 that occupies an entire city block in a historic district of Oslo and borders on Fred. Olsen Street—Olsen was open and outspoken, especially about his passion for renewable energy.

Although former associates say Olsen is a brutally tough businessman, in our discussions he never mentioned profits and rarely cited numbers when talking about his latest investments. For Olsen, renewable energy is more an ethical calling than a business imperative. His long experience in petroleum production convinces him that the world isn’t facing a shortage of oil or even a future of ultrahigh prices. But renewables are essential, he says, to counter global warming. “If this warming continues, the oceans will rise, and the place we’re sitting now, and many cities, will be under water,” says Olsen, who drives a Tesla Model S. His principal crusade is protecting the Arctic from the drilling and shipping traffic that fracture the polar icecap. “I used to fly over the North Pole, and all you saw was thick, white ice, cracked like the surface of an old painting,” he says. “Now you see lots of black water, and that accelerates the heating of the oceans.”

Olsen views himself primarily as a designer and inventor whose background in the energy business enables him to be ambitious. “My lack of a formal education is a terrific advantage,” he says in his lightly accented English. “I’m not held back by academic constraints. I think more broadly, and worry about the engineering details later.” While others wring their hands about climate change, Olsen intends to do his part to fix the problem by creating a model for scaling up renewable-energy resources. It would be just the latest chapter in a life of remarkable tales.

It was a narrow escape. On April 9, 1940, the day the Nazis invaded Norway, 11-year-old Fred, accompanied by his mother and another family, skied across the Dovre Mountains to the Atlantic fjords, where they met up with his father, Thomas. The Olsens caught a British destroyer to the Orkney Islands. “I rode into Orkney straddling a torpedo,” says Fred. The family settled in Ossining, a New York City suburb on the Hudson River, and Fred attended nearby prep schools. “I still wear the wool pants from Abercrombie & Fitch from 1942,” says Olsen. “They still fit, and they’re tough as hell.” A frequent visitor in Ossining was close family friend and fellow Norwegian Thor Heyerdahl, five years before his fabled 1947 voyage across the Pacific on the raft Kon-Tiki. “I’d see him at our pool in a bathing suit, standing in the drenching rain, steeling himself against the dangers of lightning,” says Olsen.

An adamant anti-Nazi, Thomas Olsen had pleaded in vain for Norway to arm itself against a German invasion and sent most of the family cash to the U.S. just before the Nazis took Oslo. In 1941, Thomas paid $500,000 to purchase a majority interest in a Connecticut-based manufacturer of bomb fuses for the British government, the Waterbury Clock Co. A few years later Thomas Olsen would rechristen the company Timex. He hatched the iconic name from an unusual confluence of sources. Recalls Fred: “My father always loved to noodle with words. He liked to read Time magazine, and he used a lot of Kleenex, so he put the two names together and got Timex.”

Thomas Olsen was also a great patron of the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch. When the Olsens fled Norway they left much of their collection, including a celebrated version of Munch’s famous “The Scream,” hidden in a barn, where it remained throughout the war. Fred’s much younger brother, Petter, would later win “The Scream,” and most of the family’s other Munch paintings, in a bitter inheritance battle with Fred. He sold it in 2012 to billionaire Leon Black for $120 million, then the highest price ever paid for a work of art at auction. Fred sold most of his collection in 2006 for $29.5 million, though two Munch paintings hang in his Oslo home today.

The family returned to Norway after the war, and Thomas Olsen rebuilt the shipping business, which dates from 1848, while retaining ownership of Timex. But in 1955, Thomas suffered a serious stroke, and Fred, at age 26, took charge of the family business empire.

It wasn’t too long before Olsen sensed a major opportunity. In the early 1960s discoveries of natural gas in the British sector of the North Sea convinced Olsen that the seabed between Scotland, Denmark, and Norway covered vast reserves of oil. In 1965 he formed a consortium of shipping, insurance, and industrial companies to apply for drilling licenses in Norway’s North Sea. The Norwegian Oil Consortium, or Noco, won what would become lucrative concessions. “I had the fancy thought that Norway could be a great oil nation,” he says. In 1967, Noco, along with Amoco and other partners, retrofitted an old whaling vessel to explore for oil, punching some of the first test holes in Norway’s sector of the North Sea.

The Olsens had long controlled Aker, a large shipbuilding concern. As chairman, Olsen steered Aker into the burgeoning field of building semi-submersible drilling rigs, which sit on giant pontoons. Aker produced the first semi-submersible ever built in Norway, the Ocean Viking.Phillips Petroleum leased the rig, and in 1969 it made the first oil discovery in the North Sea, in what turned out to be the massive Ekofisk field. It would become one of the largest offshore oilfields of its time, helping to attract oil majors to the region.

Inspired by the Ekofisk discovery, Olsen pushed Aker to totally transform its business. “I heard that in the Yukon gold rush, it wasn’t just the people who found gold who got rich, it was the owners of the brothels,” says Olsen. “We wanted to provide the services and products the offshore drillers needed most.” Aker’s specialty had been constructing cargo ships and tankers. Olsen decided to focus on constructing rigs specially designed for the battering waves of the North Sea. Convincing the troops provided a lasting lesson in management. “Most companies have tremendous trouble changing to another product group,” he says. “The managers fight to the end because they’re afraid they won’t hold such an elevated position in the new pyramid.” In the end he prevailed, and the super-rugged Aker H-3 rig became the workhorse of the North Sea.

Over the years Olsen has demonstrated a remarkable instinct for catching trends, riding them to the top, and exiting at the crest. Consider his timing in tankers. From the mid-1960s to the early 1970s, Olsen shed almost his entire fleet of ships in a strong market. In January 1973, Olsen observed that tanker prices had tripled in five years. Fearing a glut, he sold three tankers to GATX of the U.S. for $25.5 million, today’s equivalent of $130 million. He was both smart and lucky. Months later the OPEC crisis tripled oil prices and sank the tanker market. His run continued with Aker. In 1985 cement maker Norcem purchased Aker as oil hovered around $30 per barrel. Olsen collected some $110 million. Within a year crude prices dropped as low as $12.

Today Olsen’s businesses fall into two main categories: energy and Timex. His daughter Anette generally takes the CEO role at the family companies, with Fred serving as chairman. They’ve collaborated closely for 30 years: Fred decides what big trends to follow, and Anette heads up operations. Olsen claims only a small ownership share in his family companies, but he’s long exercised strong management control over all of them. Today those companies generate around $2.5 billion in sales and more than $500 million in cash flow.

In energy the Olsens control a network of enterprises spanning petroleum and renewables. Fred. Olsen Energy, their oil services company, owns and leases vessels to large companies such as Chevron and Anadarko. Over the past several years it’s been highly profitable, generating $395 million in cash flow after interest and taxes in 2014. (For all the Fred. Olsen companies, the period after Fred signifies that it’s an abbreviation of Fredrik.) Crude’s free fall over the past several months, however, has hurt its stock price. Since early last year, FOE’s shares have dropped from $33 to around $9, lowering the company’s market cap from $2.2 billion to $600 million.

Olsen isn’t especially concerned about the plunge in oil prices. He’s seen those patterns before. “What goes up has to come down,” he says. “But when prices drop too rapidly, they tend to rise rapidly. The drop was too dramatic, and as a result, there’s too little drilling.” Olsen foresees a world where oil hovers around $65, a price that should revive share prices in the drill rig sector. That’s if demand from China remains relatively stable. If China’s oil consumption spikes, says Olsen, he believes prices will rise well above $65.

The Olsens control Fred. Olsen Energy through a publicly traded holding company, Bonheur. Its main investments are 52% of FOE and 100% of Olsen’s two major green-energy businesses, as well as Fred. Olsen Cruise Lines, whose four ships carry almost 100,000 vacationers a year on tours of the Caribbean and other sunny locales. For now, the larger green venture is Fred. Olsen Renewables, or FOR, a builder and operator of onshore wind farms. FOR owns all the projects it develops. Its six farms in Britain supply around 7% of the nation’s wind power, and seven more sites that are approved or under construction, in Scotland and Scandinavia, will almost triple its output of electricity.

The offshore wind arm is Fred. Olsen Ocean (FOO). FOO and its subsidiaries supply all the labor and vessels required to install wind farms at sea. Unlike its sister, FOR, FOO doesn’t own the projects it builds; it’s strictly a service provider in a fast-growing arena. The fall in oil prices isn’t hurting renewables, since they benefit from rich subsidies provided by Germany and the U.K., among other nations. The wind businesses are highly profitable, generating $132 million in cash flow on $307 million in sales for 2014.

The energy side of the business also includes Harland and Wolff, the shipyard in Belfast that built the Titanic; it now designs and builds systems for both the oil and renewable-energy industries, from offshore rigs to wind turbines. Then there is Olsen’s 11,000-acre domain in Scotland, known as the Forrest Estate, where the public is invited, for a fee, to enjoy pheasant hunting and trout fishing. The rustic grounds are home to his renewables consulting branch, Natural Power, where 100 employees work in offices covered by a turf roof to conserve heat, a feature Olsen adapted from the farms of Norway.

Timex, Olsen’s second big holding, is a great brand in need of revival. Since 2010 the global watch industry has shown strong growth, advancing more than 30% to around $70 billion in retail sales. Timex, however, has missed the wave. Traditionally the privately owned manufacturer specialized in cheap, durable, mass-market timepieces. But today many younger consumers rely on their smartphones to tell time, and the just-the-basics Timex franchise has suffered. The growth area is in higher-end timepieces. Guess is the company’s premier fashion brand, and recently it has been losing ground to flashier new rivals such as Michael Kors, manufactured by Fossil. A big push into luxury has met with mixed results, leading Timex to drop its premium Valentino and Vincent Bérard brands.

Timex remains profitable, but both earnings and sales are heading the wrong way. Around 2010, Timex was earning $80 million on sales of $800 million. “Both turnover and profits are lower than they were,” says Olsen, who declines to cite precise figures.

Olsen has rescued Timex from tough times before. In the early 1980s the company was near death. Its great days on the back of a legendary ad campaign—“It takes a licking and keeps on ticking”—had vanished with astonishing speed as the company stuck to mechanical watches when the world went digital. Between 1979 and 1983, Timex’s workforce shrank from 30,000 to 6,000. And in 1984 it lost $120 million. Olsen began spending every other week in Connecticut. “I’d make calls to Europe from 3 a.m. to 8 a.m., then go to work at Timex until 6 p.m.,” he says.

His presence galvanized and terrified employees in equal measure. Each morning he’d race into the parking lot in a secondhand Oldsmobile 98 sedan, then sprint upstairs to his office. “It was like he never slept,” says one former employee. “He could be really rough when he was mad about something. He could shame you. But you knew why, and you knew you’d screwed up. If you were as passionate as he was, he loved you, but if not, you were gone.” In quieter moments Olsen would regale employees about the lost city of Atlantis or Heyerdahl’s discoveries. They called such sessions “going to the moon.”

Olsen’s passion was new products, and his inventions saved Timex. “I noticed people jogging, even in the heat in Houston,” says Olsen. “Yet the sports stores hadn’t kept up, and I thought they would.” He saw an opportunity to capitalize on a growing fitness craze and came up with the Ironman Triathlon, which by the late 1980s became the bestselling watch in America and remains a Timex staple. In 1992, Olsen pioneered another trademark feature—Indiglo, a paper-thin luminescent film that, when you touch a button, creates a green or blue night-light.

Despite its current problems, Timex retains two big advantages: prowess in technology and expertise in sports watches as the purveyor of the Ironman Triathlon. The company is blending those two strengths in a promising new product called the Timex Ironman One GPS+. It’s a combination sports and smartwatch designed for runners, and it’s the first watch that doesn’t need a mobile phone to connect to a wireless network. Runners can leave their mobile phones at home and still listen to tunes via the watch as well as track their speed and check emails. “This is a great opportunity for us,” says Anette.

So what is the value of the Olsen empire? Fred Olsen tellsFortune that he gave all the shares in his companies to trusts for Anette and his other three children, a son and two more daughters, in the 1960s. For a wealthy energy mogul, he’s a model of frugality. “I live off my salary and pension, never off my capital,” he says. “And it’s nothing like what you see in America. In Norway they don’t like people who make a lot of money.” Overall, the family’s

ownership share in the energy enterprises is less than $500 million, a big drop from last year because of the fall in shares at Fred. Olsen Energy. Given the volatile nature of oil prices, it’s more logical to base Olsen’s energy wealth on the net worth, or book equity, of the companies—the value of the ships, rigs, and other assets, minus debt. In petroleum and renewables, the family’s equity stake stands at around $800 million.

Fred’s family shares its ownership in Timex with the family of his brother, Petter, through a trust based in Liechtenstein. Timex is probably worth something more than a typical valuation of one times sales, simply because of its great brand name. So a reasonable value for Timex is $1 billion, with Fred’s family share worth $500 million. Adding their Timex holdings to the energy interests’ book value of $800 million, the family’s wealth comes to $1.3 billion or so, not including the Forrest Estate and other outside holdings. If oil prices rebound, that number will soar again.

If you think that Fred Olsen looks familiar, you have plenty of company. His narrow aquiline visage and bald pate give him an uncanny resemblance to C. Montgomery Burns, the tyrannical tycoon in the animated sitcom The Simpsons.Because of the resemblance, a rumor started years ago that the show’s creator, Matt Groening, had modeled Burns, in highly caricatured form, on Olsen. The story was frequently reported as fact in the press. It became an urban legend in Oslo and provided fodder for Timex’s unions when they feuded with Olsen. In my conversations with him, it was clear that even Olsen himself believed he’d been the inspiration for the Burns character. Now, however, Fortunecan finally lay the tale to rest. Via email, Groening toldFortune that any resemblance between Burns and Olsen is “totally coincidental.” When I informed Olsen on a recent phone call, he paused for several seconds before blurting out, “I’m thankful!”

The ultra-green Olsen viewed it as particularly unsettling to be associated with a character who owns a nuclear power plant. Most of his attention today is focused on hatching new technology in wind power. “We started with the belief that we’d take our expertise in shipping, drilling, and shipyards, and bring that know-how and talent to offshore,” he says. The offshore wind market is still tiny compared with onshore, but it’s growing far faster. Winds are stronger and steadier offshore. While it’s often hard to find locations—and secure the licenses—for onshore farms, and governments limit the size of the turbines, offshore faces no such constraints. Hence, it’s where many giant, industrial-size projects of the future will arise. Governments are hungry for wind, especially in Europe. Germany is phasing out nuclear power and plans to fill the gap largely with wind farms at sea. The U.K. wants to triple its production of renewable energy to 15% by 2020. To get there, it’s heavily promoting offshore wind. Though Europe is still the biggest offshore market, China and Japan are pledging heavy government support for wind farms that will hug their coasts.

The obstacle is offshore’s high costs, largely driven by the tremendous expense of installing massive turbines—transported by costly ships—into the ocean floor. Olsen is finding ways to radically lower the cost of installation. Among his many innovations, two are especially important. The first is a potentially huge advance in the foundations that support giant turbines. Today the most common method for installing turbines is pounding them 130 feet into the ocean floor with gigantic hammers that rent for $100,000 a day. Olsen reckoned that a Danish startup called Universal Foundation offered a far better solution, so in 2010 he bought the company. The Universal foundations operate on a suction system. A pump creates a vacuum that sinks the skirt, or bucket, into the seabed. The skirt burrows into the soil and rock like a beer mug pushed into the sand. “It reminded me of the suction anchors we used on the offshore rigs,” says Olsen. Today potential clients are extensively testing the technology offshore. The new foundations could shrink installation times, from 18 months to 12, and lower costs 20%.

Second, the Olsen team has designed a new generation of “wind carriers” that make the installation process far more efficient. “Fred was all over the design,” says Rolf Normann, CEO of Fred. Olsen Ocean. Predicting bigger and bigger turbines, he insisted on making deck space both extremely large and clear of obstruction. The installation ships have tall “jack-up” legs that loom high above the deck when the vessels are moving. When the ship is parked, the legs descend, planting their feet in the sea floor and turning the ship into a stable workstation.

Six-legged ships are common in the industry. Olsen insisted that his new ones use only four. That leaves more free space for carrying turbines. The giant crane that lifts the turbines straddles one of the legs instead of sitting on its own, saving still more deck room. The two new ships, the Brave Ternand Bold Tern, recently completed one of the most ambitious projects in offshore history—the Global Tech 1 development in the North Sea off the coast of Germany. The two ships installed 75 of the project’s 80 turbines; Global Tech will provide electricity for 330,000 households in northern Germany.

Back in his office, Olsen is reflecting on his long career, in which change has been just about the only constant. “Both products and family businesses obey life cycles,” he says. “My mother’s family was in fishhooks and horseshoe nails. Those businesses came and went. That’s why it’s so important to catch the wave, to keep innovating, keep changing.” In Olsen’s case, that’s been the blueprint for a most interesting life.

Source: The crazy, true-life adventures of Norway’s most radical billionaire